September 1, 2019

The Land Waited for the Jews

By Rabbi Meir SoloveichikWhat Nahmanides understood about Israel that Mark Twain never did.

One hundred and fifty years ago, a journalist by the name of Samuel Clemens published Innocents Abroad, the book that made his career and which remained the best-selling book in his lifetime. This was not a tale of a young boy sailing the Mississippi, but of the author himself sailing the Mediterranean to pay a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For Twain aficionados, the 150th anniversary of Innocents Abroad is a literary milestone. Yet there is an aspect of the book that perhaps only religious Jews can understand—because they can take it in tandem with the reflections of a medieval Sephardic sage who took a similar journey seven centuries earlier.

It was in 1867 that Clemens convinced a California newspaper to fund his trip on the Quaker City, a luxury cruise aboard a steamship bearing American Christians. Twain skewers much of what he sees. He pokes fun at the pilgrims with whom he was travelling. They had “dreamed all their lives of some day skimming over the sacred waters of Galilee and listening to its hallowed story in the whisperings of its waves, and had journeyed countless leagues to do it.” But they then insist on bartering with the Arab boatman because they thought the fare was too high. He mocks, as well, many of the traditional religious sites, including a spot in the Holy Sephulcre known as the burial place of Adam, the first man.

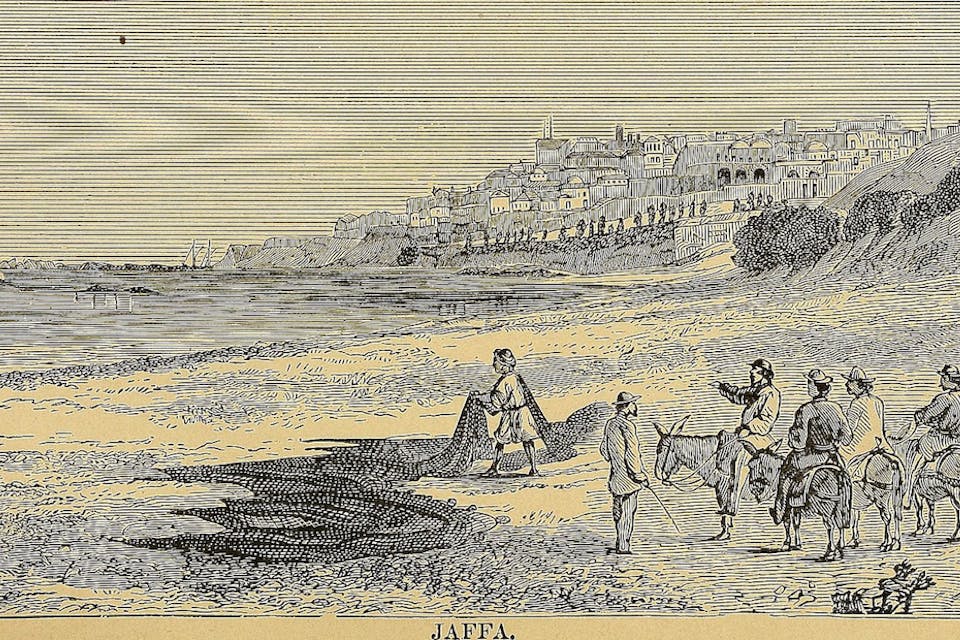

Yet the centerpiece of his biting wit is the anti-climactic nature of the place itself. The land supposedly flowing with milk and honey was anything but. In the Galilee, Twain saw here and there some “evidence of cultivation,” at most “an acre or two of rich soil studded with last season’s dead corn-stalks.” Yet the closer they came to Jerusalem, “the more rocky and bare, repulsive and dreary the landscape became.” No sight is more “tiresome to the eye,” he reflected, “than that which bounds the approaches to Jerusalem.” Palestine, he concluded, “sits in sackcloth and ashes,” and he cites the suggestion that the Israelites could have seen it as a goodly land only because of their “weary march through the desert.”