November 15, 2022

The Prime Minister and the Minyan

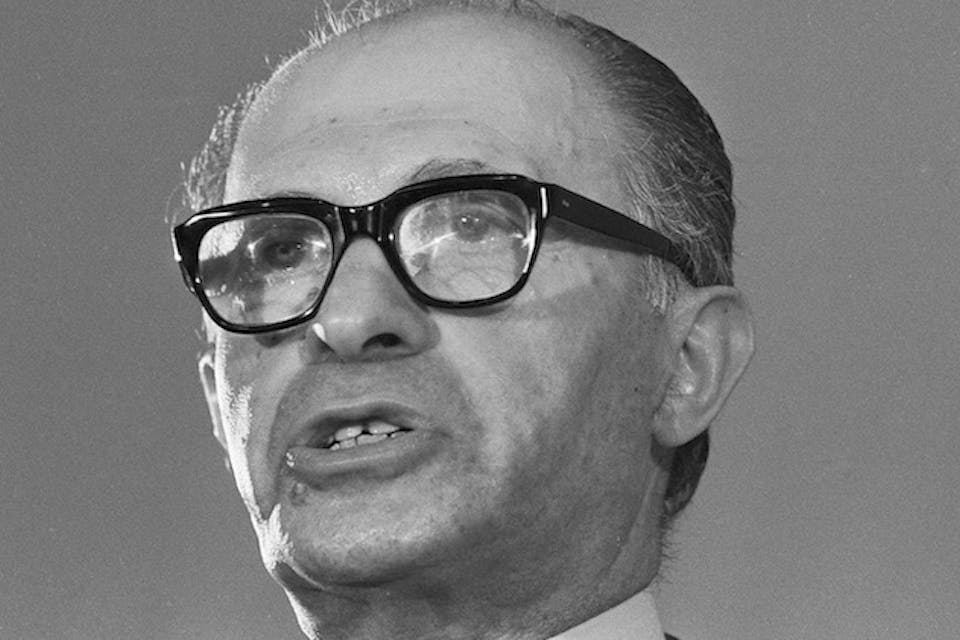

By Rabbi Meir SoloveichikAmong Israel’s founders, only Begin sensed the key role that tradition would play in the future Israeli society.

If there was a moment that captured what became known as the mahapach—the political upheaval that marked the rise of the longtime back bencher Menachem Begin to the prime ministership of Israel in 1977—it was a private one in Begin’s office, one witnessed by Begin’s friend Hart Hasten. Following an election in which he had emerged victorious, Begin was engaged in assembling a governing coalition when the members of a Haredi party burst into his office, upset over a matter pertaining to the political horse-trading. Begin sat silently as they expressed their agitation, and then he calmly responded in Yiddish: Rabbosai, hobn ihr shoin gedavent minha (Gentlemen, have you already prayed the afternoon service)? Stunned by the unexpected query, the Orthodox men paused and then replied that they had, in fact, not yet engaged in this obligatory ritual. So, at Begin’s urging, a minyan, or prayer quorum of 10, was formed in his own office, featuring Begin, Hasten, the Orthodox Knesset members, and Begin’s chief of staff, Yehiel Kadishai. By the time the service had concluded, tempers had subsided, and, bound by a shared reverence for a millennia-old faith, Begin and his future coalition members resumed negotiations with equanimity.

It’s worth keeping this story in mind as we analyze the recent elections in Israel and the decades-long trends that have produced the country’s 37th government. Every aspect of the scene in Begin’s office would have come as a profound shock to David Ben-Gurion, the man who man oversaw Israel’s birth. For Ben-Gurion, Begin was a figure whose right-wing minority party deserved no recognition; the worldview that Begin had imbibed from his mentor Ze’ev Jabotinsky represented, in Ben-Gurion’s estimation, an element of Zionism’s past, not its future. And despite the fact that Begin was the leader of the opposition, Ben-Gurion never called him by his name, referring to him instead only as “the man sitting next to Member of Knesset Bader.” Ben-Gurion even refused to facilitate the moving of Jabotinsky’s body to Israel for reburial (the great Revisionist leader had died in New York in 1940). Begin was forced to wait until 1964 and the premiership of Levi Eshkol to secure Jabotinsky’s reinterment in the Holy Land.

Ben-Gurion would certainly be surprised, to say the least, to learn that in 2022, Jabotinsky’s movement would make Likud, the party of Jabotinsky’s heir, the largest party in Israel—while Labor, the heir to his own socialist party, would only barely make it into the Knesset.