December 1, 2017

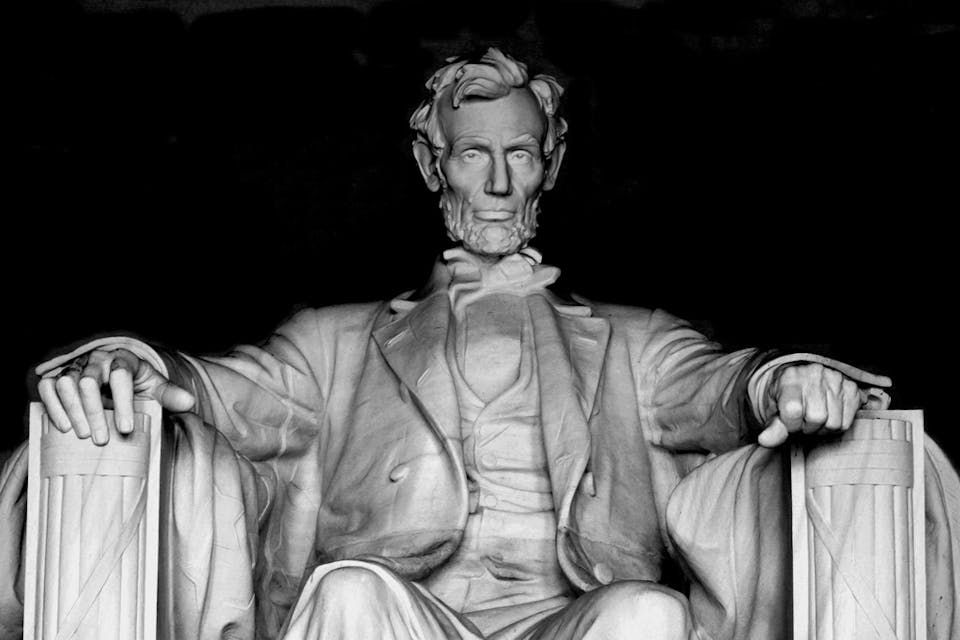

The Theologian of the American Idea

By Rabbi Meir SoloveichikHow Abraham Lincoln taught us to think about America and its civil war.

If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South, this terrible war, as the woe due to those by whom the offence came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a Living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “The judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether.”

Lincoln’s second inaugural is the most remarkable speech in American history. Its exquisite words appear to have been penned not by a statesman but by a theologian who sees the punishing hand of God in an ongoing war and who implicitly calls his countrymen to repentance. To find its parallel, one must look not to other admirable examples of English wartime rhetoric—Shakespeare’s Agincourt or Churchill’s Dunkirk—but to the Hebrew Bible, with whose words Lincoln concluded the paragraph cited above. Yet a century and a half after the second inaugural was delivered, and with our society once again debating the Civil War, it is painfully clear that we have forgotten some of its central lessons.

Standing on the Capitol steps in 1865, with Union victory a certainty, one would have expected a president to celebrate the valor of his soldiers triumphantly, to rejoice in the coming end of the war and in the justice of his cause. Yet Lincoln does no such thing. Instead, like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel during Israel’s wars with foreign powers, he seeks to explain the designs of Providence in producing so much death and destruction. He finds the answer in what he believes is the sin of both North and South, a sin that lies in the origins of America. On the wonderful website What So Proudly We Hail, Caitrin Keiper rightly calls Lincoln’s thesis “a comprehensive but harrowing theodicy of American history stretching back before the nation’s founding.” No one killed in the Civil War was personally involved in the Atlantic slave trade or the inclusion of slavery in the Constitution, “but it is for these actions, as much or more than any current and particular sin of slave-holding, for which everyone has now to pay.” Just as the Founders’ achievements are our patrimony, so too, for Lincoln, “their guilt is everyone’s inheritance as well—the sins of the fathers visited on the children to the third and fourth generation.”