June 17, 2021

Yiddish is a Language of Faith

By Rabbi Meir SoloveichikNo matter how hard some try to disconnect it, Yiddish is inseparable from Judaism.

Early in 2021, a niche online argument made its way onto the front page of the Wall Street Journal, complete with a catchy headline: “Designing a Flag for Yiddish Takes Chutzpah.” The cause of the disagreement was the announcement by Duolingo, a website for learning languages, that it would release a course for Yiddish. Usually, the symbol for a language would be the flag of its home country: France, Italy, Japan. Yiddish, however, was a language of exile; the Israeli flag would represent Hebrew, not Yiddish. What, then, should serve as its symbol? Suggestions abounded, including that the website should “just put a bagel on it,” or that it should feature a “fiddler on a roof.”

The contretemps is intriguing because it inspires the inquiry: What makes Yiddish unique? If every language has its individual character, what exactly characterizes Yiddish? Jews give many answers to this, but not all are equally correct. The Journal reports that one suggestion for the Duolingo symbol was the word “kvetch” surrounded by a circle; this reflected the thesis put forward by Michael Wex in his bestselling Born to Kvetch, which argues that Yiddish provides a way of “seeing the world in cataract-colored glasses.” But does “kvetch” truly capture Yiddish? It is true, of course, that Yiddish is a magnificent language for anyone who wants to say something unkind. As Leo Rosten noted, “little miracles of discriminatory precision” exist in the difference between a nebekh, a shlep, a shmendrik, a shlump, a klutz, a yold, a shnook, a Chaim Yankel, a bulbenik, a shoyteh, a shlemazel, and a shlemiel; all of these terms describe pathetic people, but there are different reasons as to why they are pathetic.

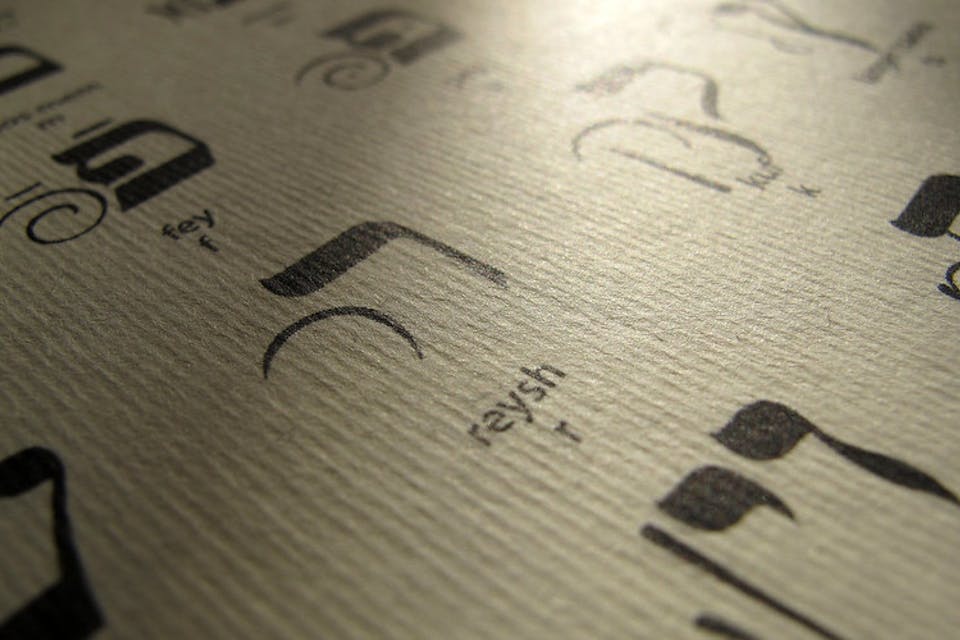

Yet to reduce Yiddish in this way is to commit a calumny against a language that is not about negativity. Isaac Bashevis Singer was surely correct when, in his Nobel Prize address, he argued that there is in Yiddish “a gratitude for every day of life, every crumb of success, each encounter of love.” The most insightful summation of Yiddish’s character was put forward by Max Weinreich, the 20th century’s greatest scholar of the language, who argued that Yiddish embodies the Derekh HaShaS, or “the way of the Talmud.” By this he meant not that the Talmud was written by Yiddish speakers, but that Yiddish trains its speakers to see the entire world from a Talmudic perspective, so that every aspect of reality is described in similes and metaphors that refer back, in some profound way, to the life of halakhic Judaism. Wex more accurately captures Yiddish’s essential nature when he focuses not on kvetching but on the fact that “the Talmud is nothing less than Yiddish in utero. The Jews who initiated the transmutation of German into Yiddish were those Jews most deeply connected to Jewish law, people for whom the categories and mental processes of halokhe, of Jewish law, were practically second nature.”