August 18, 2020

Adin Steinsaltz’s Glimpse into the Way That All Jewish Languages Work

Whether it’s Judeo-Arabic, or Judeo-Italian, or Judeo-Spanish, or the Judeo-German better known as Yiddish, they all mix in varying amounts of Hebrew.

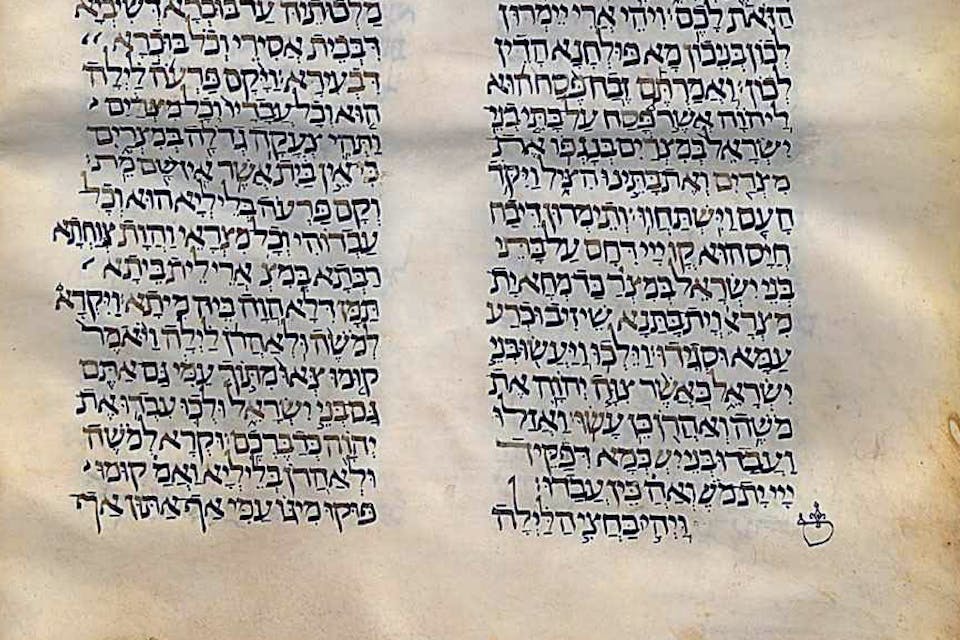

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, who died last week at the age of eighty-three, was a towering figure in the field of Jewish learning, with some 60 books to his credit in such diverse areas as Talmud, Kabbalah, and Jewish philosophy—an all the more astonishing output when one considers that he had no Jewish education to speak of until he was a teenager. Yet of all his contributions, the one having the greatest impact is not a book he authored. It is his translation into pure Hebrew of the entire Babylonian Talmud, a huge work of dozens of volumes written in a mixture of Hebrew and Aramaic, the now nearly extinct language spoken by the Middle East’s Jews in the Talmudic period.

Although Aramaic is a Semitic language closely related to Hebrew (one might compare the distance between them to that between Italian and Spanish), it is not for the most part intelligible to the Hebrew reader untrained in it. Hebrew, too, of course, was far from universally understood by Jews over the ages, yet a familiarity with the Bible and the prayer book gave many Jews a basic knowledge of it that enabled them to grapple with such all-Hebrew texts as the Mishnah, the Talmud’s first, shorter, and simpler part. The Talmud’s second and far lengthier part, however, the Gemara, with its large Aramaic component mixed with Hebrew, remained a sealed work for all lacking a rabbinic education.

The Steinsaltz Talmud, therefore, which has been retranslated since its publication into other languages, including English, has been truly revolutionary in its opening up of the Gemara to the ordinary Jew, both in Israel and the Diaspora. And yet one needs to be aware not only that it is, like all translations of great works, a mere approximation of the original, but that it is even more of an approximation than other works, because it cannot in itself convey the Gemara’s unique bilinguality. Translated into pure Hebrew, let alone English, from its Hebrew-Aramaic mélange, it loses the atmosphere of switching back and forth between the two languages that is typical not just of talmudic discourse but of Jewish life throughout history.