May 19, 2015

Fiction and Foreign Policy

To the president, foreign policy isn't just about safeguarding the country. It's also, as the Iran deal makes clear, about fashioning a creative personal narrative of the effort.

In his memoirs, Duty, former Secretary of Defense Robert Gates tells a story that could only have occurred in the Obama White House. In February 2011, as crowds occupying Tahrir Square in Cairo demanded the ouster of Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak, a debate swirled over the proper American response: should the U.S. force Mubarak to abdicate, or support his plan to manage an orderly transition of power over the next seven months?

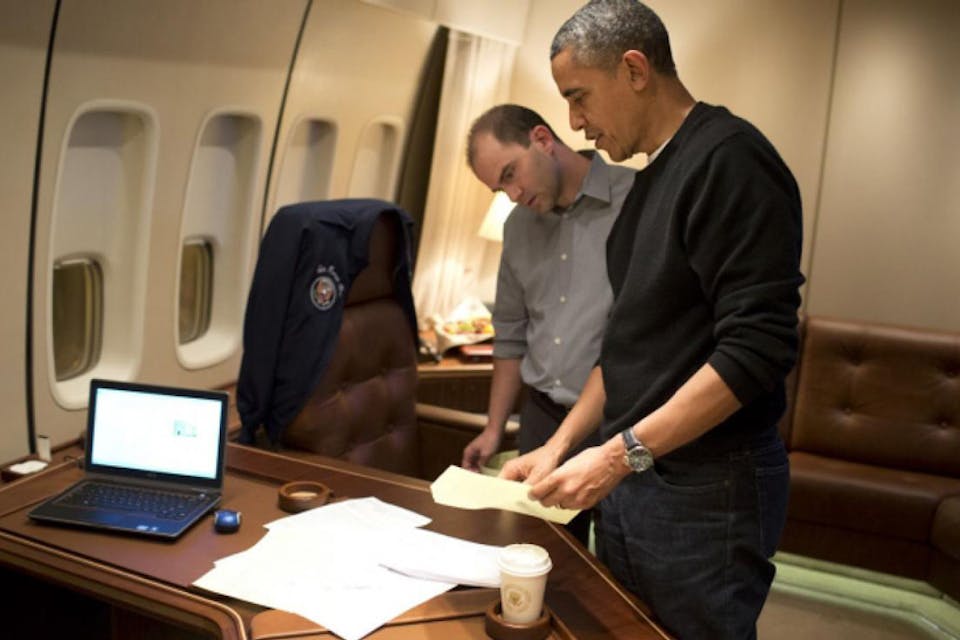

On one side stood Gates and the other principal members of the National Security Council. Mubarak, they argued, though a dictator, had been a reliable ally for 30 years, and toppling him would unleash chaos in Egypt, with no guarantee that the forces replacing him would be sympathetic to Washington, to America’s regional allies, or to democracy. On the other, pro-ouster side stood White House staffers vocally represented by Ben Rhodes—who, though only in his early thirties, bore the grand title of Assistant to the President and Deputy National Security Advisor for Strategic Communication and Speechwriting. In addition to his youthfulness, Rhodes had limited experience in international politics; his master’s degree was in creative writing, and his official role was that of a “communicator,” or spinmeister.

In the end, the president sided with the Rhodes faction, thus placing himself, in a phrase that soon emerged from the White House, “on the right side of history.” That side led, as Gates had warned, to a political vacuum in which the only established and well-organized party was the Muslim Brotherhood, which soon took power.