June 29, 2022

How Jews Came Under Socrates’s Spell

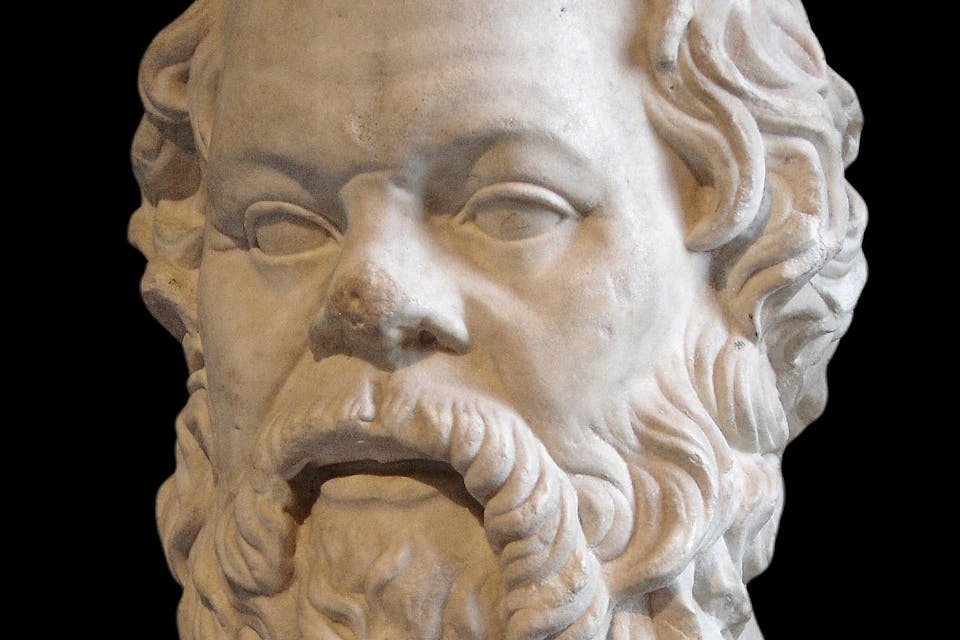

By Alexander OrwinAn impressive new book explores how a community rooted in faith and law has grappled with the preeminent classical rationalist.

Socrates (469-399 BCE) personifies our notion of a universal figure. Despite leaving nothing in writing, his relentless quest for the philosophic truth in the marketplaces and schools of Athens has resonated across time and place, while his trial and placid death at the hands of the city, ostensibly for corrupting the youth with impiety, served only to increase his posthumous renown. Not only did Socrates teach Plato and Aristotle, whose works form the bedrock of the Western philosophical canon, but he also influenced Rome through Cicero, the Islamic world through Alfarabi and Averroes, and Christendom through Aquinas, Dante, and their many successors. Even modern European thinkers who claim to reject much of the legacy of antiquity, such as Rousseau, Adam Smith, and Nietzsche, were fascinated by the figure of Socrates. In contemporary universities, the constant ebb and flow of trendier subjects has not dislodged Plato’s Republic, a dialogue in which Socrates in the main character, from its spot near the top of lists of the most frequently taught books. Winston Churchill, a notoriously poor student whose preoccupation with urgent, life-and-death matters of war and politics fostered a healthy contempt for the “talkative professor” that was Socrates, nonetheless asked the right question: “Why had his fame lasted through all the ages?”

Readers of this magazine might want to know how the Jews figure in this story. As a people, the Jews might well share Churchill’s resistance to Socratic questioning, for their own peculiar reasons. A community whose stubborn adherence to its faith and law has allowed it to survive centuries of both intense persecution from the surrounding society and intense pressure to assimilate into it, would naturally rebuff philosophic efforts to question its beliefs and practices from within. Yet the pull of Socratic texts and ideas was too strong to reject outright. An impressive new book by the Israeli philosopher and historian Yehuda Halper, Jewish Socratic Questions in an Age Without Plato, describes how the best and brightest Jewish minds of the Middle Ages came under Socrates’s spell.

This does not mean that the Jews swallowed Socrates whole. The adroit thinkers treated in Halper’s book all managed to wear their Socratic baggage lightly and unpack it in a selective fashion carefully designed to lessen the impact of its contents on their faith. They were aided in this endeavor by the limited availability of genuine Socratic texts in their time: while vestiges of Platonic dialogues and other sayings attributed to Socrates survived, the full Platonic corpus did not. Knowledge of the Greek language had gradually disappeared, so medieval readers were dependent on translations into Arabic, but we cannot verify, even today, the form in which dialogues such as the Apology and Republic were translated. It was therefore surprisingly easy for some Jewish intellectuals to portray Socrates as a wise but pious ascetic.