June 4, 2019

Making a Space for God

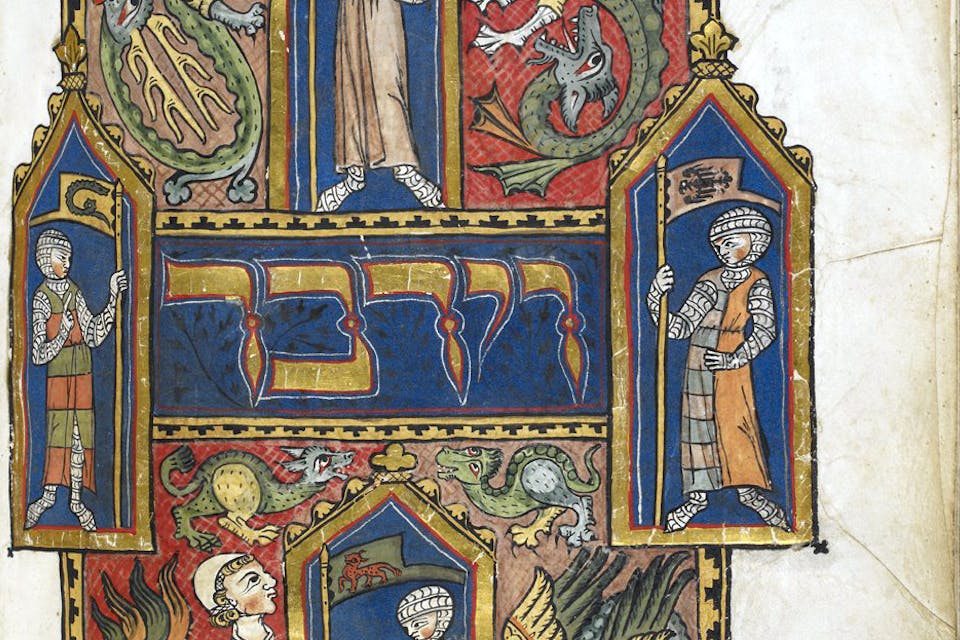

How the 14th-century creators of an illustrated Pentateuch managed to reflect both the Jewish and the Christian worlds they lived in.

Every year, the Torah portion of B’midbar (“In the Desert”)—the first reading in the biblical book known in English as Numbers—coincides roughly with the festival of Shavuot (“Weeks”), celebrated this year on next Sunday and (in the diaspora) Monday, and traditionally referred to as “the time of the giving of our Torah.”

The background, recounted in the book of Exodus, is this: seven weeks after leaving Egypt, the Israelites receive, at Sinai, not only the Torah but also the awesome revelation of God’s presence. Now, in Numbers, that transcendent moment of closeness with God has been extended into history as a living presence in the divinely-ordained Tabernacle, just as it will eventually become a living presence in the Temple in Jerusalem and, ultimately, in every space in which Jews gather to pray.

How much space, exactly, need be dedicated to this purpose? As little as arba amot—four cubits—will suffice, a cubit being equal to the span from one’s elbow to the tip of the middle finger, and four square cubits being roughly equivalent to six square feet. And here’s the rub: no single person’s cubit is identical in dimensions to another’s. Everyone makes—everyone is commanded to make—his or her own space for God.