June 9, 2016

How Did Yiddish Words Make Their Way into German?

A centuries-old tale of complicated, ambivalent, and, sometimes, covertly intimate relationships between a largely anti-Semitic Christian society and its Jewish minority.

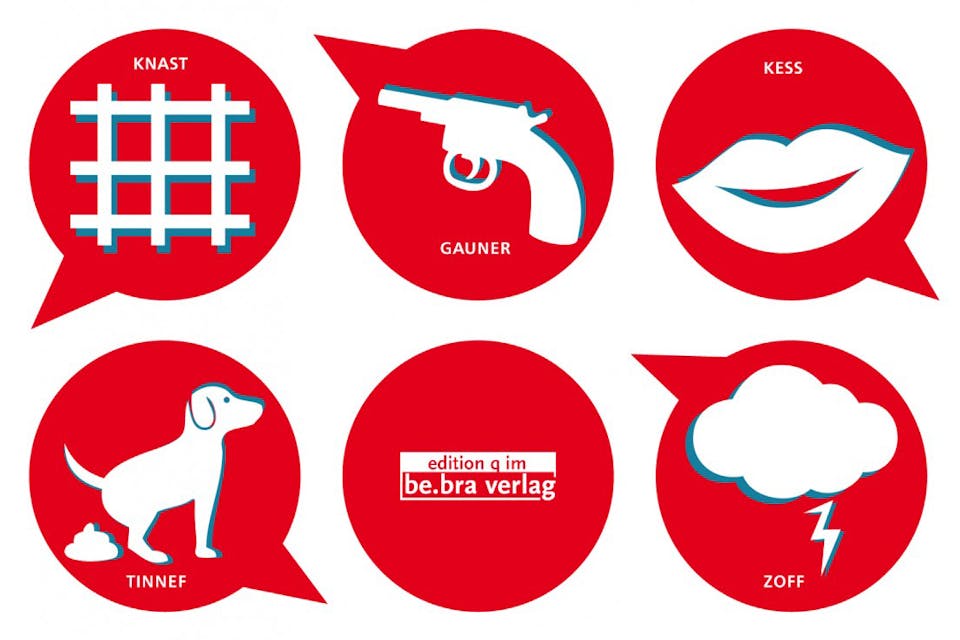

Mysteriously, a newly published book was delivered to me by courier mail the other day with no indication of who sent it. Written by the German linguist Christoph Gutknecht, it’s entitled Gauner, Grosskotz, Kesse Lola: Deutsch-Jiddische Wortgeschichten (“Gauner, Grosskotz, Kesse Lola: German-Yiddish Word Histories”), and in it are over 60 entertaining mini-essays by the author about West European Yiddish-derived words in the German language and the complex stories of what happened to them there. (West European Yiddish, substantially different from the more familiar East European dialects that developed from it, was once spoken by Jews in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and elsewhere.)

It wouldn’t be difficult to come up with a similarly long list of East European Yiddish words in contemporary American English, but accounts of their English lives would be, on the whole, simple and straightforward. Words like “maven,” “hutzpah,” “shmooze,” “shlep,” “tchotchke,” and the like were all introduced into the American vernacular in the 20th century by Yiddish-speaking immigrants from Eastern Europe; have continued to have more or less the same meanings in English that they had in Yiddish; and have rarely been altered beyond easy recognition by phonetic change, grammatical inflection, or compounding with other English words. Although they give impressive proof of Jewish acculturation in an accepting American society, their linguistic trajectories have been no more remarkable than those of “pizza,” “kindergarten,” “chic,” and other modern borrowings from foreign languages.

Not so, West European Yiddish words in German. Their presence there often goes back hundreds of years, is frequently veiled or obscured entirely by the vicissitudes of linguistic change, and tells a tale of complicated, ambivalent, and, sometimes, covertly intimate relationships between a largely anti-Semitic Christian society and its Jewish minority. Moreover, whereas Yiddish words that have made their way into English have Hebrew, Germanic, and Slavic etymologies in roughly the same proportion as is found in Yiddish’s overall vocabulary, the provenance of Yiddish words in German is overwhelmingly Hebraic.