May 26, 2021

The Jewish Background of the Pentecostal Practice of Speaking in Tongues

According to the Talmud, when God handed down the commandments, he handed them down in every language at once.

Last week was Shavuot, and this past Sunday was the Christian holiday of Pentecost that is linked to Shavuot. The word Pentecost, which is often used to denote Shavuot itself, comes from Greek pentecoste, “fiftieth” a reference to the commandment in the book of Leviticus to count seven weeks (shavu’ot) or 49 days from the second day of Passover and hold a “holy convocation” (mikra kodesh) on the 50th day. In Christianity, the 50 days ending with Pentecost are counted from Easter Sunday.

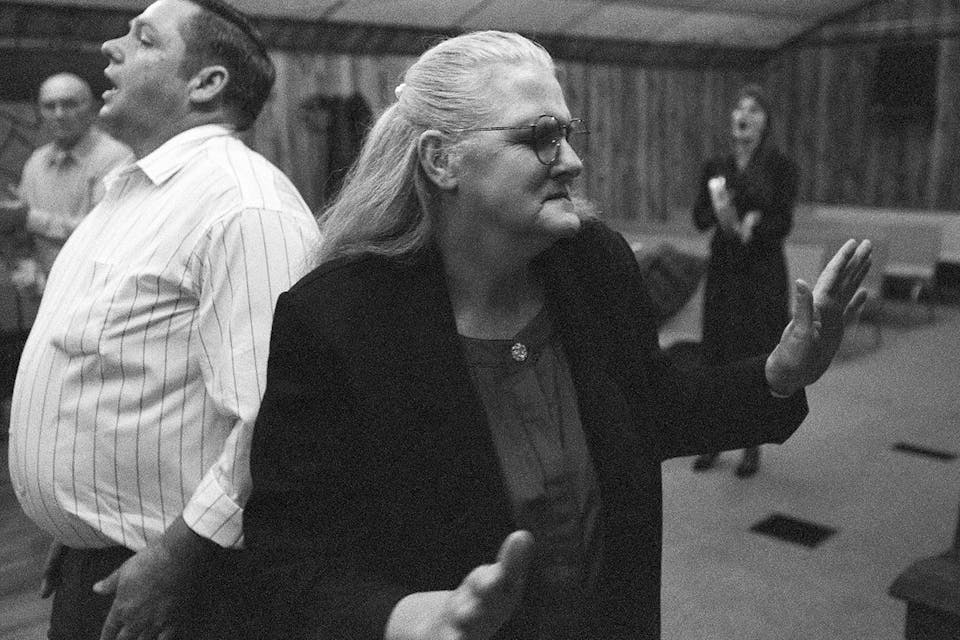

The English word “Pentecostal,” however, does not refer primarily to either the Jewish or the Christian holiday. Rather, it signifies any one of various Christian churches or denominations characterized by highly emotional prayer, ecstatic singing, dancing, and drumming, trance states, and what known as “speaking in tongues”—or to linguists, as “glossolalia” (from Greek glossa, tongue, and laleo, to talk or babble). Speaking in tongues is a practice that goes back to Chapter 2 of the New Testament book of Acts of the Apostles, which tells of the first Pentecost or Shavuot celebrated in Jerusalem by Jesus’ disciples, all Jews and Aramaic-speaking Jews from the Galilee, shortly after their teacher’s death. In the translation of the King James Version:

And when the day of Pentecost was fully come, they were all with one accord in one place. And suddenly, there came a sound from heaven as of a rushing, mighty wind, and it filled all the house where they were sitting. And there appeared unto them cloven tongues like as of fire, and it sat upon each of them. And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit, and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit gave them utterance. And there were dwelling at Jerusalem Jews, devout men, out of every nation under heaven. . . . And they were all amazed and marveled, saying one to another, Behold, are not all these which speak Galileans? And how hear we every man in our own tongue, wherein we were born?