July 18, 2018

The Prophet Whose Glorious Words Permeate Jewish Consciousness

Isaiah's unforgettable language serves much the same role in spoken Hebrew that Shakespeare’s does in English.

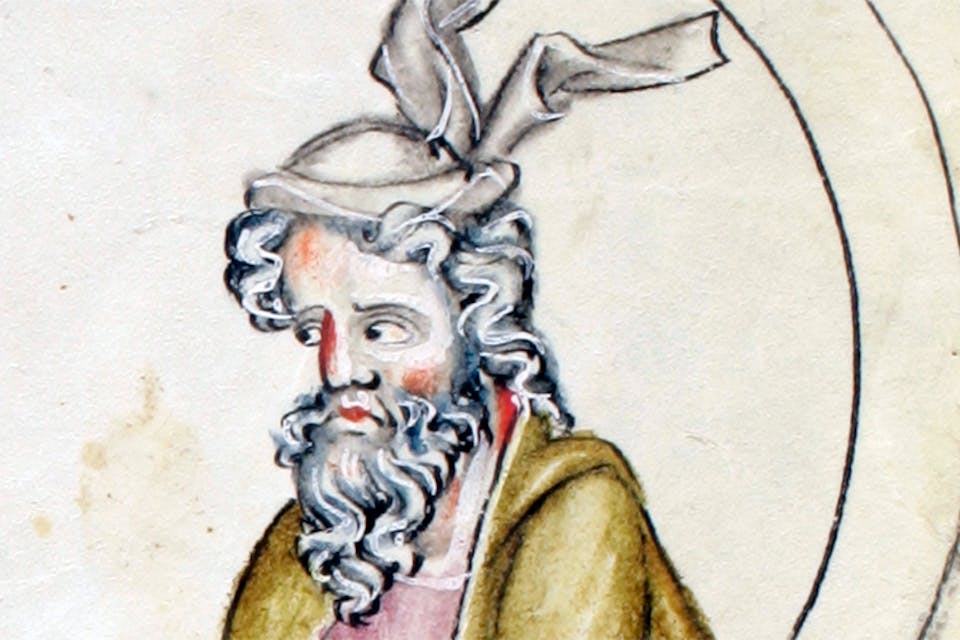

The haftarah (prophetic reading) for this Sabbath is the first chapter of the vast book of prophecies attributed to Isaiah son of Amotz, who lived in the 8th century BCE and whose career overlapped with the desuetude and destruction of the Northern Kingdom of Israel by the Assyrian empire, and the deportation of much of its populace. No doubt the chapter is placed first in the book not because it is the earliest of Isaiah’s prophecies but because, in its blend of consolatory sweetness and acrid, stinging light, it is the most representative. Indeed, the Sabbath on which it is read each year—namely, the Sabbath preceding the fast of the Ninth of Av, which commemorates the destruction of both temples—is known (after the book’s opening words) as shabbat ḥazon, the Sabbath of “Isaiah’s vision.”

The modern reader of the prophetic books of the Bible—as opposed to its epic or historical parts—must struggle to define their genre. Are they satires, and frequently very bitter ones? Are they invocations to greater moral probity? Are they consolatory visions of a better future? This is certainly true for readers of Isaiah. Nobody can quite decide how to place it, what exactly its darker prophecies refer to, and to what extent, if any, these prophesies were confirmed. In the view of many traditional Jewish commentators, some were fulfilled immediately, while the fulfillment of others was postponed until the days of the Second Temple and his consolations await fulfillment in the messianic era.

So if we’re not looking to Isaiah for his forecasts, what do we look to him for? Jews look to Isaiah, I would argue, principally for the glorious language in which he portrays both the degradations of his own time and the redemption that will arrive in God’s good time. And that language is on overpowering display not just once a year, in this week’s haftarah, but in more haftarot than have been taken from any other prophet. These include not only the seven haftarot of consolation read in the weeks between Tisha b’Av and Rosh Hashanah but also about ten others read during the rest of the year. Extracts from his prophecies are also prominently placed at key points in the liturgical cycle: on the morning of Yom Kippur, on a New Month if it falls on the Sabbath, in the afternoon prayer of a public fast day (in the custom of many communities), and in the diaspora on the final day of Passover. Nowadays Isaiah is also read on Israel’s Independence Day, at least by those who celebrate it in synagogue.