August 2025

A College Guide for the Perplexed

With anti-Semitism on the rise and the humanities in decline, how can young Jews pick the right university?

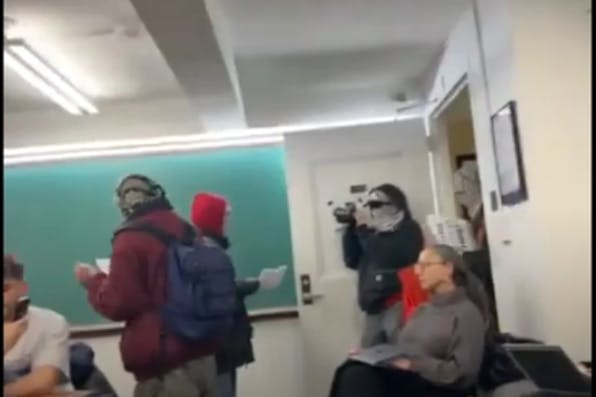

Over the past year and a half, the problems of many American universities have been front and center of our national conversation: the tolerance towards radical student groups and lawless campus behavior, the transformation of many humanities and social science departments into monocultures of ideological indoctrination, the misguided obsession with race and gender and the administrative bloat to enforce it, and now the targeting of Jews and Israel as the sin-stained enemies of the Progressive project to attack Western civilization with some perverse new strain of Red-Green anarchy. Of course, conservative intellectuals have been alarmed about the problems of the American university for decades—if not since 1951, when a young William F. Buckley published God and Man at Yale decrying the secularization of academic culture, then at least since 1987, when the philosophy professor Allan Bloom made himself into a celebrity with The Closing of the American Mind, arguing that a small-souled relativism had replaced the deeper quest for truth. This was followed by Roger Kimball’s Tenured Radicals, Dinesh D’Souza’s Illiberal Education, and from there an unbroken stream of analysis and critique. Meanwhile, the cultural problems on campus have only deepened, and in recent years a widening range of professors, deans, and college presidents, including many self-professed liberals, have written their own academic laments for the betrayal of liberal learning and free inquiry that once defined our best institutions of higher learning.

As a new school year approaches, it seems clear that we are living through a moment of academic reckoning—and, as a consequence, a moment of potential reform and opportunity. The excesses of campus activism have captured public attention, with a rolling tempo of news stories about the latest fines and settlements with the federal government over campus misdeeds. Employers are questioning whether a diploma from one of the highest-ranked universities represents more of a liability than an asset for a job applicant. Many are beginning to wonder whether once-revered degrees from schools like Harvard and Columbia are really trustworthy measures of an actual education and reliable indicators of sound character. And, as often happens when Western nations and cultures are in crisis, it is Jews who find themselves at the center of the civilizational struggle—and Jewish parents and Jewish students who are most urgently grappling with what college now holds in store. After decades of seeing the most elite universities as our temples, American Jews are wondering if we are living through yet another age of destruction and dispersion.

The anxious Jewish chatter is endless. At countless social gatherings and Shabbat tables, in numerous online forums and WhatsApp groups, Jewish parents are asking themselves and each other how to navigate college selection for their children. Those who two years ago wondered, “If my fifteen-year-old maintains her grades, can she win admissions to Harvard or Columbia?” now ask, “If my daughter gets into Columbia, do I really want her going there?” The father initially thrilled that his son was accepted to George Washington University or UCLA may now ask himself, “Will he be safe? Subject to anti-Semitic harassment? Or worse, will he come home for Thanksgiving wearing a keffiyeh and shouting at me and my wife for supporting genocide because we planted a tree in Israel in honor of his bar mitzvah?”

Responses to August ’s Essay

August 2025

The Future of Higher Education and the Jews: A Symposium

By The Editors

August 2025

How Jewish Studies Became a Tool of Adversarial Culture

By Ruth R. Wisse

August 2025

The Future of Universities Must Be Built on Firm Values

By Daniel Diermeier

August 2025

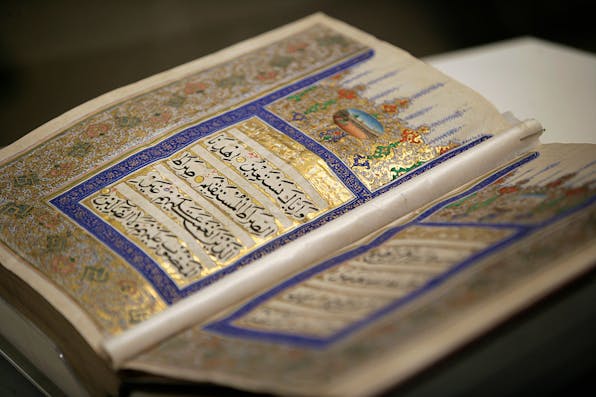

Western Civilization and the Jews: A Shared History

By Steven H. Frankel

August 2025

The Quest for Wisdom, Truth, and Virtue at the University of Dallas

By Jonathan J. Sanford

August 2025

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

By Bella Brannon

August 2025

Saving American Universities Requires Cracking Down on Foreign Funding

By Danielle Pletka

August 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

By Eitan Webb

August 2025

The Moral Collapse on Campus Is a Result of the Hollowing Out of the Humanities

By Alexander S. Duff

August 2025

Return American Universities to Their Religion-Friendly Roots

By Liel Leibovitz

August 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

By Ari Berman

August 2025

The Universities and the American Crisis

By Ben Sasse

August 2025

The Campus Intifada Is a Golden Opportunity for Those Who Study Israel Seriously

By Avi Shilon

August 2025

With No Easy Fixes for Middle East Studies, It’s Time for New Programs

By Robert Satloff

August 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

By Michael Hochberg