August 25, 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

Even in STEM fields, the forces that shape decision-making for students, faculty, and administrators push them towards academic mediocrity and leftist politics.

An undergraduate degree from the most prestigious schools in the United States is, as evidence of educational achievement, worthless. The hardest thing anyone does on these campuses as an undergraduate is get admitted.

This is now a widely recognized fact in the technology world: no sensible manager would even consider hiring candidates out of an elite American college solely because of their grades and the school’s prestige. This is not true of a degree from the top schools in China, which remain significantly meritocratic, where judging students by their grades has real value. In fact, I recently had a conversation with a former admissions officer for an Ivy League medical school who told me that the admissions committee routinely disregards grades from Princeton as being a result of systematic grade inflation.

To put a finer point on it, receiving a degree from Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, or Yale is a strong indicator of socioeconomic class, of having done well in high school, and of a willingness to tolerate four years of progressive indoctrination. It’s an indication of a willingness to pay approximately the median cost of a house, plus four years of opportunity cost, to engage in high-grade social networking and prestige signaling—both of which, to be sure, can be incredibly valuable.

Responses to August ’s Essay

August 2025

The Future of Higher Education and the Jews: A Symposium

By The Editors

August 2025

How Jewish Studies Became a Tool of Adversarial Culture

By Ruth R. Wisse

August 2025

The Future of Universities Must Be Built on Firm Values

By Daniel Diermeier

August 2025

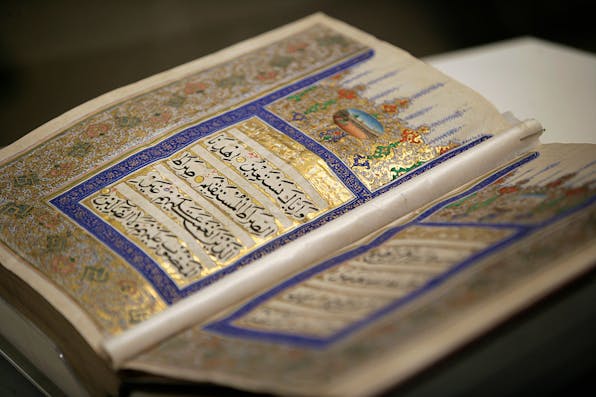

Western Civilization and the Jews: A Shared History

By Steven H. Frankel

August 2025

The Quest for Wisdom, Truth, and Virtue at the University of Dallas

By Jonathan J. Sanford

August 2025

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

By Bella Brannon

August 2025

Saving American Universities Requires Cracking Down on Foreign Funding

By Danielle Pletka

August 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

By Eitan Webb

August 2025

The Moral Collapse on Campus Is a Result of the Hollowing Out of the Humanities

By Alexander S. Duff

August 2025

Return American Universities to Their Religion-Friendly Roots

By Liel Leibovitz

August 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

By Ari Berman

August 2025

The Universities and the American Crisis

By Ben Sasse

August 2025

The Campus Intifada Is a Golden Opportunity for Those Who Study Israel Seriously

By Avi Shilon

August 2025

With No Easy Fixes for Middle East Studies, It’s Time for New Programs

By Robert Satloff

August 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

By Michael Hochberg