About the Author

Liel Leibovitz, a journalist, media critic, and video-game scholar, is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine.

August 18, 2025

We have a golden opportunity to remember what higher education is for.

I’ve made somewhat of a career out of announcing the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad state of American higher education. In 2019—when the sentiment was much less popular—I wrote a piece for Tablet Magazine called “Get Out,” in which I analyzed at some length the strange death of the university, and argued that Jews (or, for that matter, Americans) need no longer bother enrolling in college. Mutually accrediting mediocrities, I wrote, are now in charge, and they reward not free and unfettered intellectual pursuits but sniveling subservience to their pet ideologies, making our children mad, dumb, and mean.

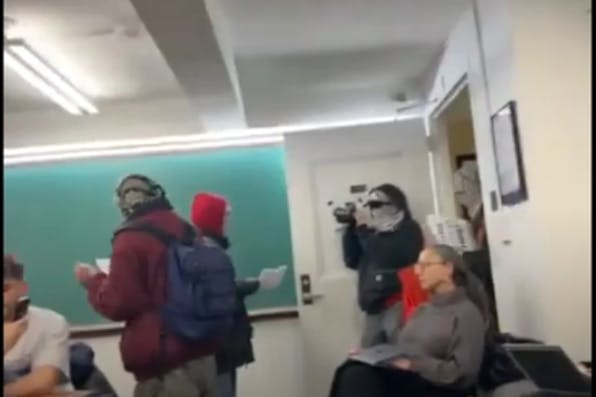

At the time, I was dismissed as a kooky alarmist. Later, when the goon squads started marching on the quad, waving the flags of Hamas and Hizballah, I was vindicated, which, annoyingly, brought me no pleasure. I was thrilled to see President Trump take some much-needed steps to curb the worst abuses, even though I remain keenly aware that the problems that plague academia are many and deeper than anything even an army of executive orders might amend.

And yet, if there’s one thing that repels me more than the good-natured liberals who propose to cure this mighty malady with mild tinctures—just toss more money into yet another anti-anti-Semitism program, or supply incoming freshmen with better pro-Israel talking points—it’s the sullen alarmists who cackle that things are just too broken and therefore oughtn’t be fixed at all. We Jews are anything but victims; when faced with ruination, we must do more than sit by the relics and weep, or rush to punish the destroyers. We must build anew.

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

August 2025

I’ve made somewhat of a career out of announcing the terrible, horrible, no good, very bad state of American higher education. In 2019—when the sentiment was much less popular—I wrote a piece for Tablet Magazine called “Get Out,” in which I analyzed at some length the strange death of the university, and argued that Jews (or, for that matter, Americans) need no longer bother enrolling in college. Mutually accrediting mediocrities, I wrote, are now in charge, and they reward not free and unfettered intellectual pursuits but sniveling subservience to their pet ideologies, making our children mad, dumb, and mean.

At the time, I was dismissed as a kooky alarmist. Later, when the goon squads started marching on the quad, waving the flags of Hamas and Hizballah, I was vindicated, which, annoyingly, brought me no pleasure. I was thrilled to see President Trump take some much-needed steps to curb the worst abuses, even though I remain keenly aware that the problems that plague academia are many and deeper than anything even an army of executive orders might amend.

And yet, if there’s one thing that repels me more than the good-natured liberals who propose to cure this mighty malady with mild tinctures—just toss more money into yet another anti-anti-Semitism program, or supply incoming freshmen with better pro-Israel talking points—it’s the sullen alarmists who cackle that things are just too broken and therefore oughtn’t be fixed at all. We Jews are anything but victims; when faced with ruination, we must do more than sit by the relics and weep, or rush to punish the destroyers. We must build anew.

But how? And what to build? It’s a question that requires more breadth than even a Mosaic symposium can provide, but we have to begin somewhere, and any vision of a thriving future must, I believe, rest on the twin pillars that have traditionally made American academia excel: pursuit of truth and love of country.

If you want to understand the history of American higher education (its stately rise, its dizzying fall) look no further than the two Hebrew words Yale University—established in 1701 by the Congregationalist clergy of the Connecticut Colony—chose to engrave on its coat of arms: Urim v’Tummim, the same words associated with the breastplate worn by the high priest in the Temple of old, used to divine the will of God. Just in case your Hebrew was rusty, Yale applied a bit of Latin, too, to let you know what the school was all about: Lux et Veritas, went its motto, light and truth.

To those of us who entered academia’s gates in the 80s, 90s, or later, after the invasion of the heathenish French intellectuals who declared truth suspect and banished it from the classroom, the idea of an institution dedicated to truth—and recognizing, at that, God as the ultimate truth-giver—is nothing short of astonishing. As William F. Buckley observed in God and Man at Yale, a book which was written in 1951 but might as well have been published yesterday afternoon, the story of the last few decades in American higher education is the story of snuffing out the religious fires that have illuminated the world since time immemorial and replacing them with chillier stuff, like sterile thought exercises designed to “problematize” rather than truly to understand.

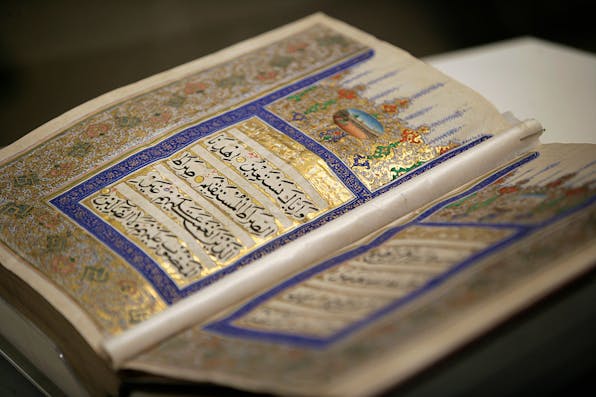

Our first step, then, must be returning American universities to their religion-friendly roots. By which, of course, I do not mean that all schools must now assign the complete Sihot, or discourses, of the Lubavitcher rebbe as required reading (though perhaps not a bad idea), but simply re-commit to the elementary idea that faith is a force that gives us meaning, that prayer is a basic human need, that looking heavenward for inspiration and hope has done the species more than a bit of good. And then, rather than either ignore these core human feelings altogether or examine them in courses with titles like “Medieval Christian Patriarchy and the Oppression of Gender Non-Conforming Pagans” (I made that one up, but, really, is it that much of a stretch?), universities ought to explore these yearnings in earnest, which would also mean hiring faculty members who don’t despise the Creator and those of us who follow His law.

Such re-commitment to taking religion seriously would go a very long way towards bringing down the current collegiate inflammations. But there’s another, and arguably even more crucial step, which is re-imagining American universities as, well, American institutions.

Once upon a time, not too long ago, it was perfectly understood that the purpose of an American university was to prepare its graduates to live and thrive as Americans, citizens of the greatest nation on earth, flush with privileges and bound by civic duty. That is changing rapidly. Take, for example, my ignominious alma mater, Columbia University. Based on the school’s own data, in 2011, 25 percent of its student body consisted of foreign students; by 2021, the number spiked to 37 percent, and it continues to rise dramatically.

This should come as no surprise. Foreign students are more likely to pay full tuition, and are therefore financially more appealing to admissions officers. They also reflect the reality in which Columbia’s graduates increasingly live, one of global citizenship with allegiance given to the technocratic, multinational corporations and organizations that keep the meritocracy comfortably numb. Speaking as a former international student myself—born and raised in Israel—we would do very well not only to curb significantly the number of foreigners we allow in our ivory towers, but also to reorient the curriculum to reflect a deeper understanding of, love for, and dedication to this great and godly nation.

Imagine, for example, requiring all rising juniors to take a semester off and spend it in some corner of America they would never have otherwise seen, taking a break from the Marxism and oat-milk lattes of their leafy campuses and living, for three or four months, with the struggling youth of downtown Chicago, or the workers of Flint, Michigan, or the ranchers out in Wyoming, or on a reservation in South Dakota. Imagine instructing these young Americans that their future lies not in some finance job in London or a consulting gig in Hong Kong, but here, at home, because, as the Talmud so wisely teaches us, we must always prioritize our own before looking out to the great big world.

But, I hear some grumbling, our career-minded teens will never go for such soft, altruistic stuff! Again, we’ve only to consult the data: repeatedly and without fail, when asked what it is they most look forward to in college, incoming students emphasize not the social experience or the eventual benefits of a high-paying job, but meaning. They crave a big shining why, some greater purpose that their anxious parents, focused so strongly on bottom lines and pay stubs and upward mobility, have neglected. This is also why so many young and impressionable men and women end up in the clutches of monstrous terror-loving hate groups on campus: they offer a sense of moral direction, however perverse. It’s now on us to give these seekers something better to believe in, and nothing has ever been or will ever be better than love of God and country.

Let us, then, keep the ululations to a minimum. Let us work swiftly to expel the violent thugs from campus, and restore true academic freedom to our institutions. But let us also take this golden opportunity, at this moment of total and abject ruination, to ask ourselves the only question that matters—what is academia truly for?—and remind ourselves that we once had terrific answers that served us very well. With a bit of courage and a lot of imagination—qualities never in short supply in America—we can make American universities great again.

Liel Leibovitz, a journalist, media critic, and video-game scholar, is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine.

Unlock the most serious Jewish, Zionist, and American thinking.

Subscribe Now