August 18, 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

What Chabad knows about Jews on campus.

In a recent conversation about Jewish life at elite universities, someone asked me, “At what point do we just give up?” The question wasn’t an expression of cynicism, but of exhaustion. At institutions where Jewish enrollment is statistically declining, where Israel is increasingly demonized, and where religious expression often feels out of step with prevailing campus culture, it’s tempting to look at the landscape and wonder whether it’s time to invest elsewhere.

But to give up is to misunderstand the stakes, and to miscalculate the important successes already unfolding on campuses. And standing stubbornly, and joyfully, against this tide is Chabad.

The reason is simple, even if it sounds radical: Chabad doesn’t take its cues from numbers. It takes its cues from faith: faith in the Jewish soul, in the vitality of Torah, and in the enduring power of presence. That’s why, even as others lament shrinking rosters or shifting identifications, Chabad sees something else: packed Shabbat dinners, vibrant Jewish learning at midnight, big crowds at menorah lightings in the middle of finals, and students who never thought they had a place in Jewish life discovering not just a seat at the table, but a home.

Responses to August ’s Essay

August 2025

The Future of Higher Education and the Jews: A Symposium

By The Editors

August 2025

How Jewish Studies Became a Tool of Adversarial Culture

By Ruth R. Wisse

August 2025

The Future of Universities Must Be Built on Firm Values

By Daniel Diermeier

August 2025

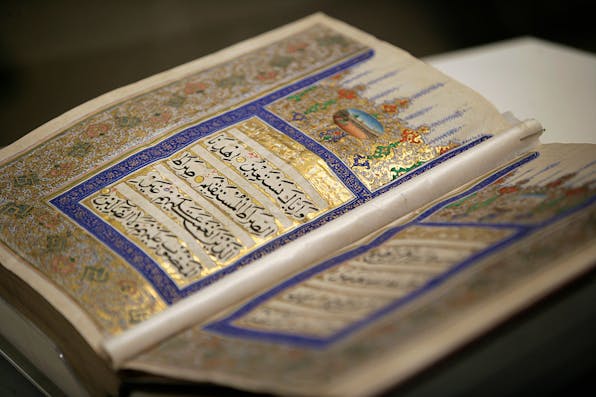

Western Civilization and the Jews: A Shared History

By Steven H. Frankel

August 2025

The Quest for Wisdom, Truth, and Virtue at the University of Dallas

By Jonathan J. Sanford

August 2025

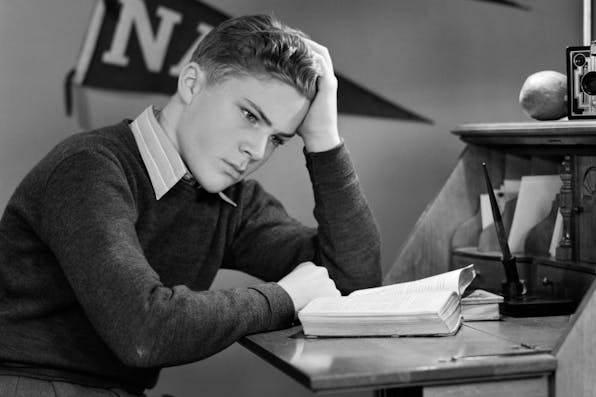

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

By Bella Brannon

August 2025

Saving American Universities Requires Cracking Down on Foreign Funding

By Danielle Pletka

August 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

By Eitan Webb

August 2025

The Moral Collapse on Campus Is a Result of the Hollowing Out of the Humanities

By Alexander S. Duff

August 2025

Return American Universities to Their Religion-Friendly Roots

By Liel Leibovitz

August 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

By Ari Berman

August 2025

The Universities and the American Crisis

By Ben Sasse

August 2025

The Campus Intifada Is a Golden Opportunity for Those Who Study Israel Seriously

By Avi Shilon

August 2025

With No Easy Fixes for Middle East Studies, It’s Time for New Programs

By Robert Satloff

August 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

By Michael Hochberg