August 25, 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

While the American university loses sight of its purpose, the future looks bright for faith-based schools.

The great American university is in decline. With decreasing enrollment, ideological polarization, and an erosion of public trust, the very idea of the university is increasingly under attack. But the formula for its salvation is strikingly simple: a return to the model of classical education upon which it was originally built. This homecoming would not just provide a shared knowledge base to create an intergenerational community of learners, but would also grant universities a robust framework for shaping their responses to the obstacles and opportunities of tomorrow.

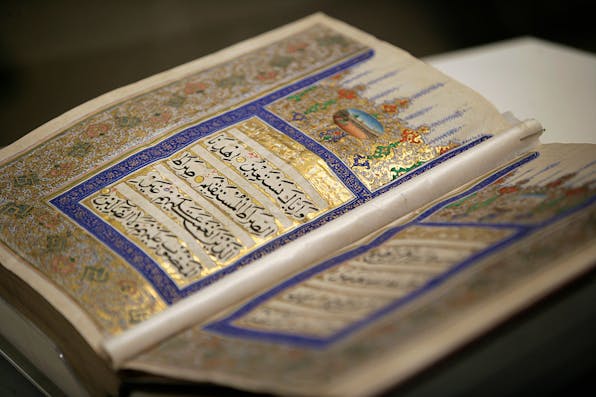

We need not look far for inspiration. Jewish tradition provides a strong blueprint for how to engender thoughtful and rooted communities of learners who are cognizant of what came before them, and of their own roles in the transmission and creation of scholarship and ideas. While this may sound like second nature to some, what often goes unspoken in current debates about campus climate is that universities themselves have lost sight of their purpose. Sometime in the final quarter of the 20th century, under the sway of postmodern relativism, curricula were revised and the mission of educating students through seeking truth and promoting virtue became passe. In many universities today, students do not see themselves as heirs to a great tradition and are not bound to each other by the exploration of foundational texts. By and large, these students do not see themselves as having anything of substance in common with their peers, much less with their predecessors. They have become unmoored and unrooted, which explains in part the rapid increase in anxiety, loneliness, and mental-health risks among college students.

By contrast, the millennia-old Jewish educational example continues moving and inspiring generations of students. This stems from a singular model of learning: rather than coming to campus to get accredited and depart, Jewish learners arrive at study houses and yeshivot to connect and to dwell.

Responses to August ’s Essay

August 2025

The Future of Higher Education and the Jews: A Symposium

By The Editors

August 2025

How Jewish Studies Became a Tool of Adversarial Culture

By Ruth R. Wisse

August 2025

The Future of Universities Must Be Built on Firm Values

By Daniel Diermeier

August 2025

Western Civilization and the Jews: A Shared History

By Steven H. Frankel

August 2025

The Quest for Wisdom, Truth, and Virtue at the University of Dallas

By Jonathan J. Sanford

August 2025

Universities Need Teachers Who Want to Teach, and Students Willing to Learn

By Bella Brannon

August 2025

Saving American Universities Requires Cracking Down on Foreign Funding

By Danielle Pletka

August 2025

Jews Shouldn’t Give Up on Universities, and Neither Should America

By Eitan Webb

August 2025

The Moral Collapse on Campus Is a Result of the Hollowing Out of the Humanities

By Alexander S. Duff

August 2025

Return American Universities to Their Religion-Friendly Roots

By Liel Leibovitz

August 2025

To Make the Academic Desert Bloom, Look to Religion

By Ari Berman

August 2025

The Universities and the American Crisis

By Ben Sasse

August 2025

The Campus Intifada Is a Golden Opportunity for Those Who Study Israel Seriously

By Avi Shilon

August 2025

With No Easy Fixes for Middle East Studies, It’s Time for New Programs

By Robert Satloff

August 2025

The Perverse Microeconomics of the American University

By Michael Hochberg